David Salle: Works on paper

On view: JANUARY 18 to APRIL 28, 2024

Opening Reception: Saturday, January 20, 2023, 6-8p

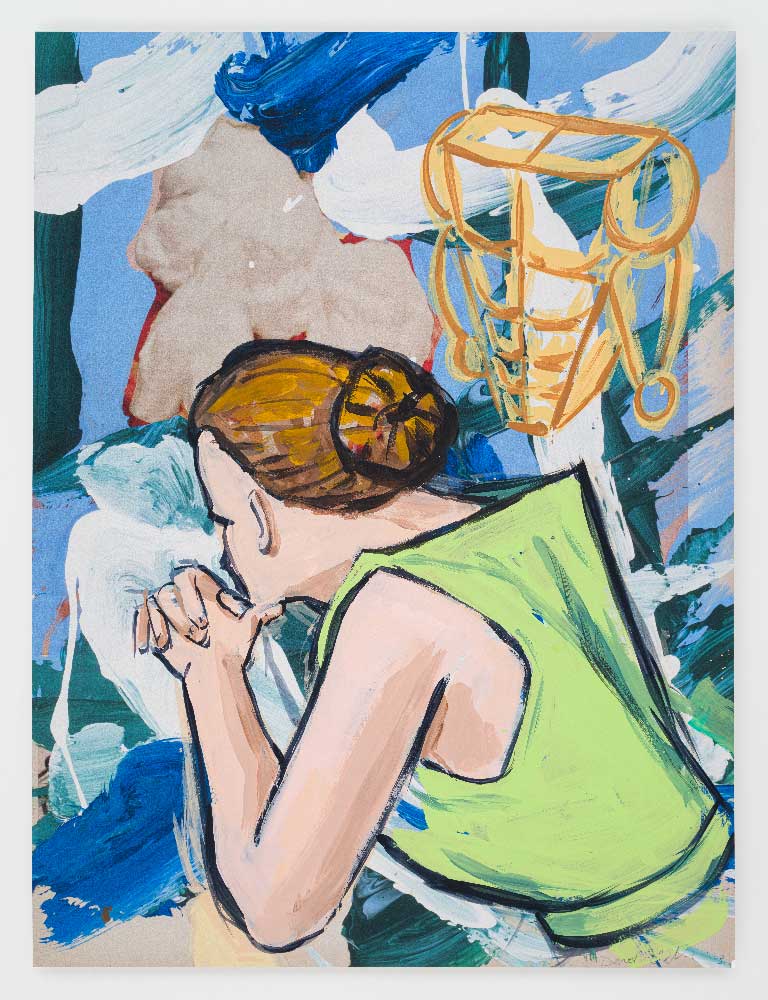

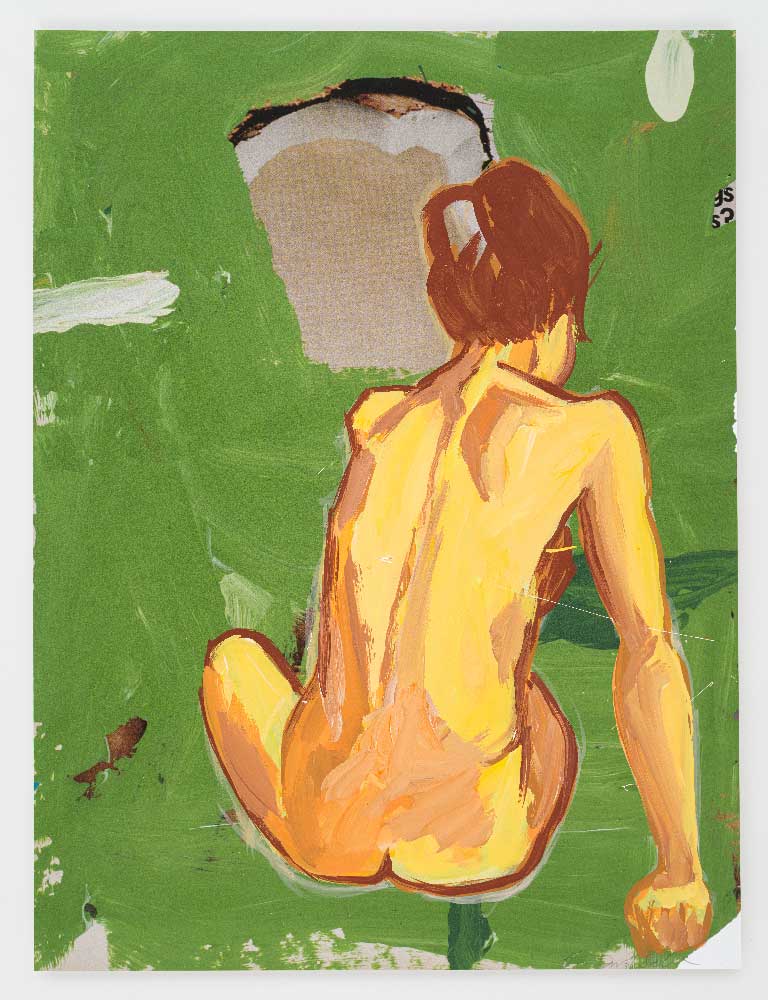

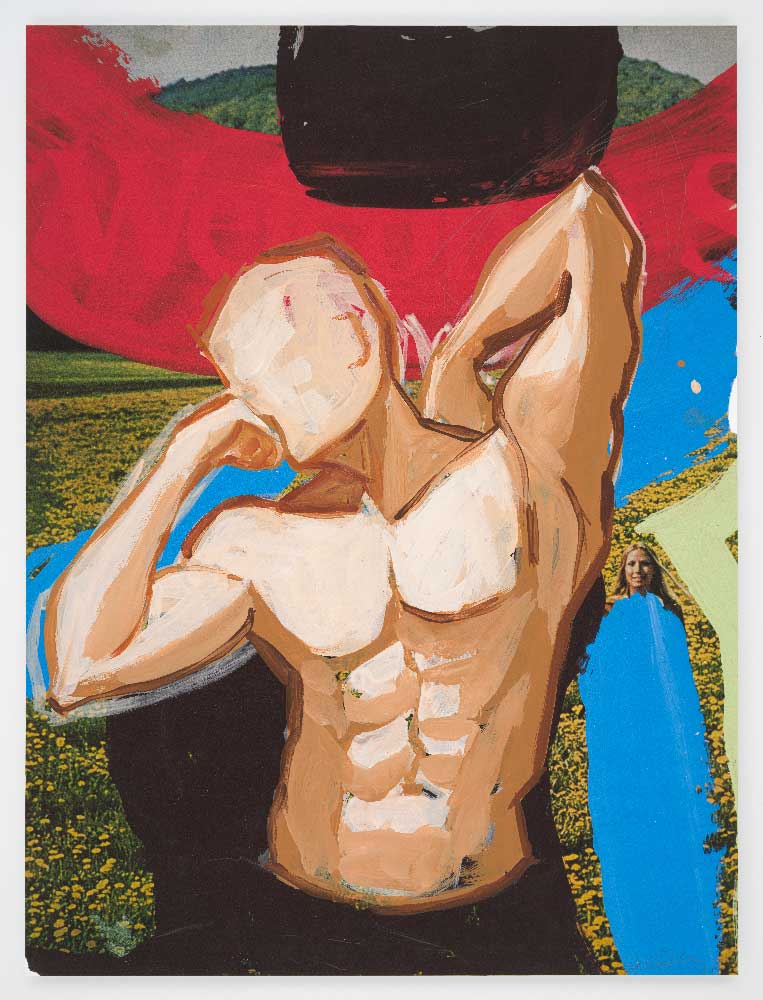

Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, Nyack, NY, is pleased to open an exhibition of new work by David Salle. The exhibition, DAVID SALLE: WORKS ON PAPER, includes the first presentation of a selection of figural paintings executed in 2023.

Opening Reception: Saturday, January 20, 2023, 6-8p

Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center, Nyack, NY, is pleased to open an exhibition of new work by David Salle. The exhibition, DAVID SALLE: WORKS ON PAPER, includes the first presentation of a selection of figural paintings executed in 2023.

David Salle is one of the most versatile and influential contemporary artists, and his expansive talent encompasses painting, photography, printmaking, and stage design. He is also a prolific essayist and is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books.

“Salle is described as an artist's artist,” says Kathleen Motes Bennewitz, Edward Hopper House Museum Executive Director. “We are honored to feature his new work in galleries within the historic home of another iconic artist, providing an interesting venue to delve into Salle’s artistic dialogue with Edward Hopper.”

“Salle is described as an artist's artist,” says Kathleen Motes Bennewitz, Edward Hopper House Museum Executive Director. “We are honored to feature his new work in galleries within the historic home of another iconic artist, providing an interesting venue to delve into Salle’s artistic dialogue with Edward Hopper.”

|

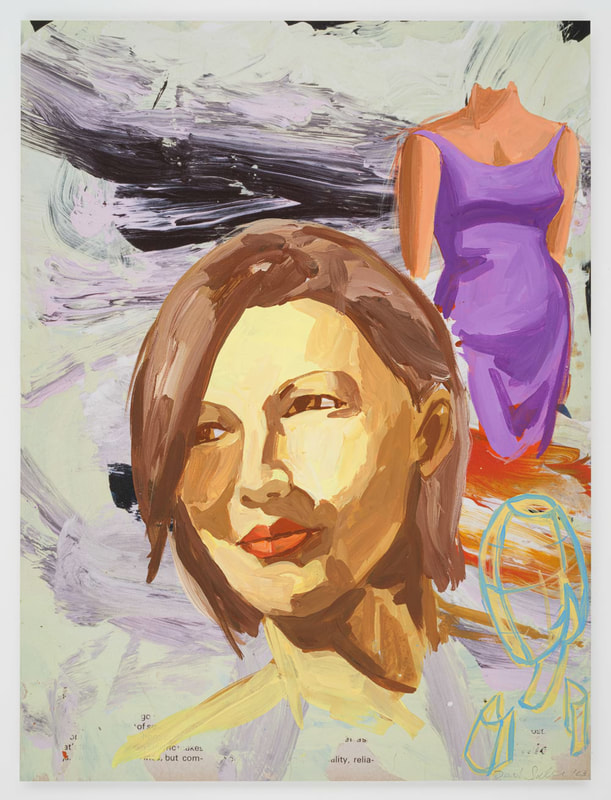

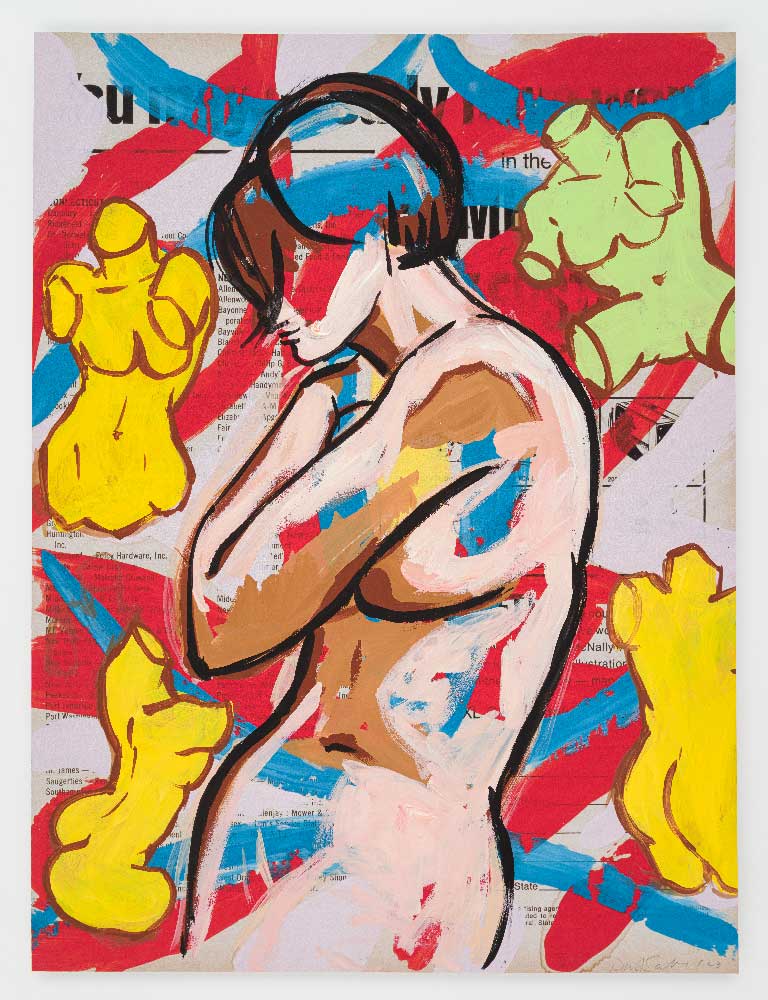

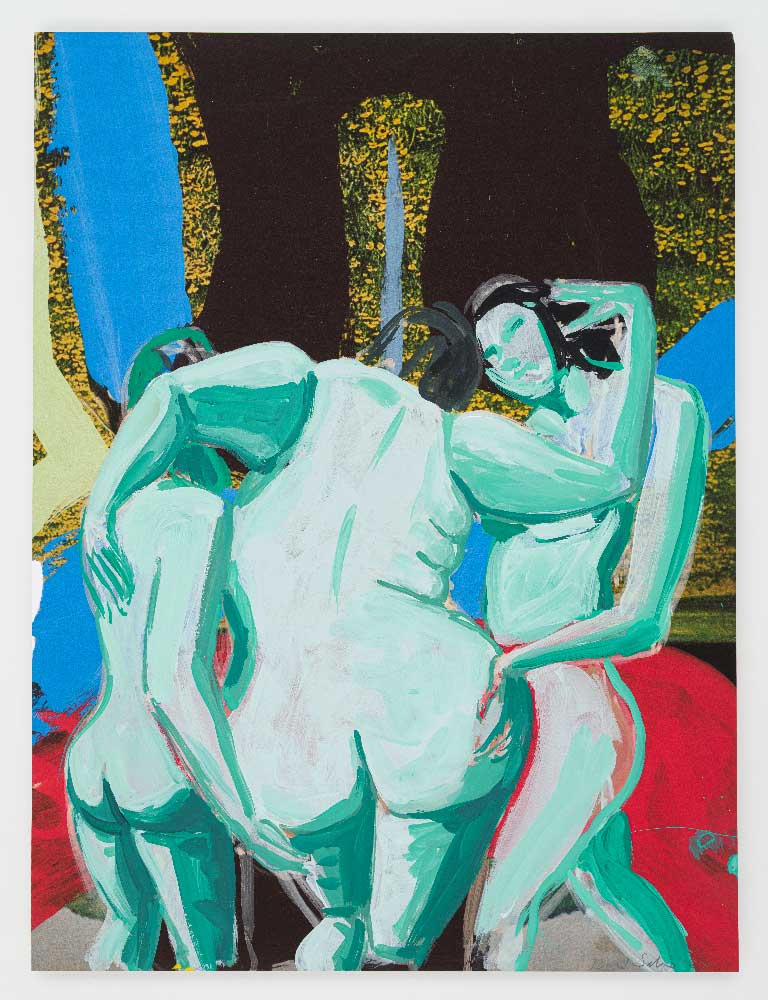

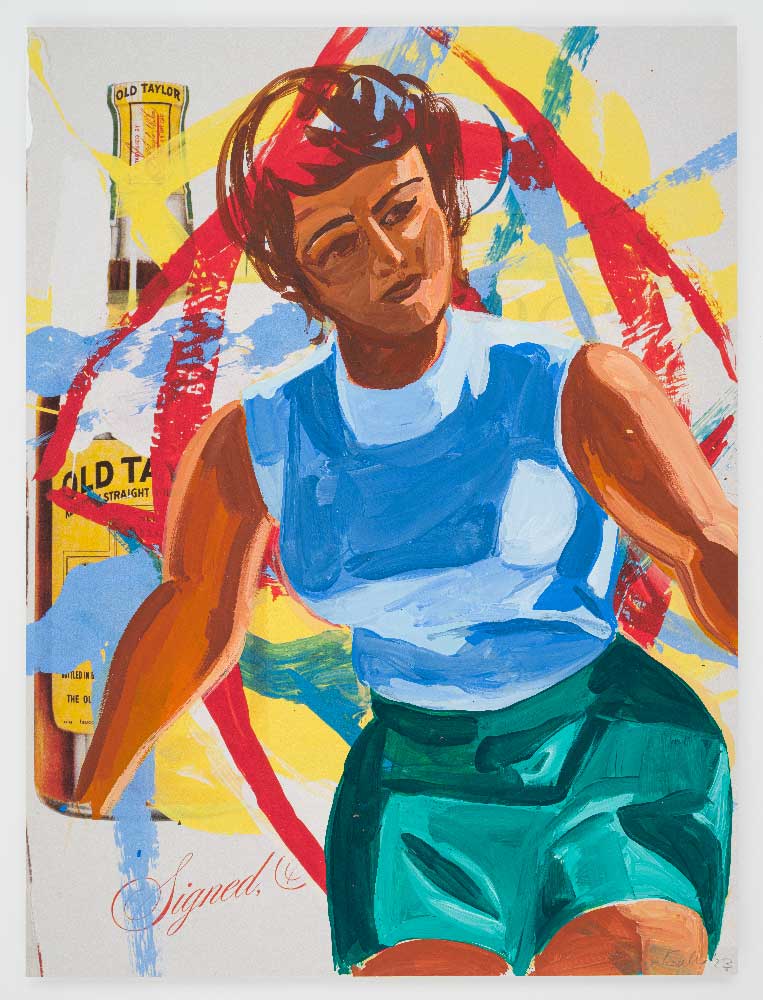

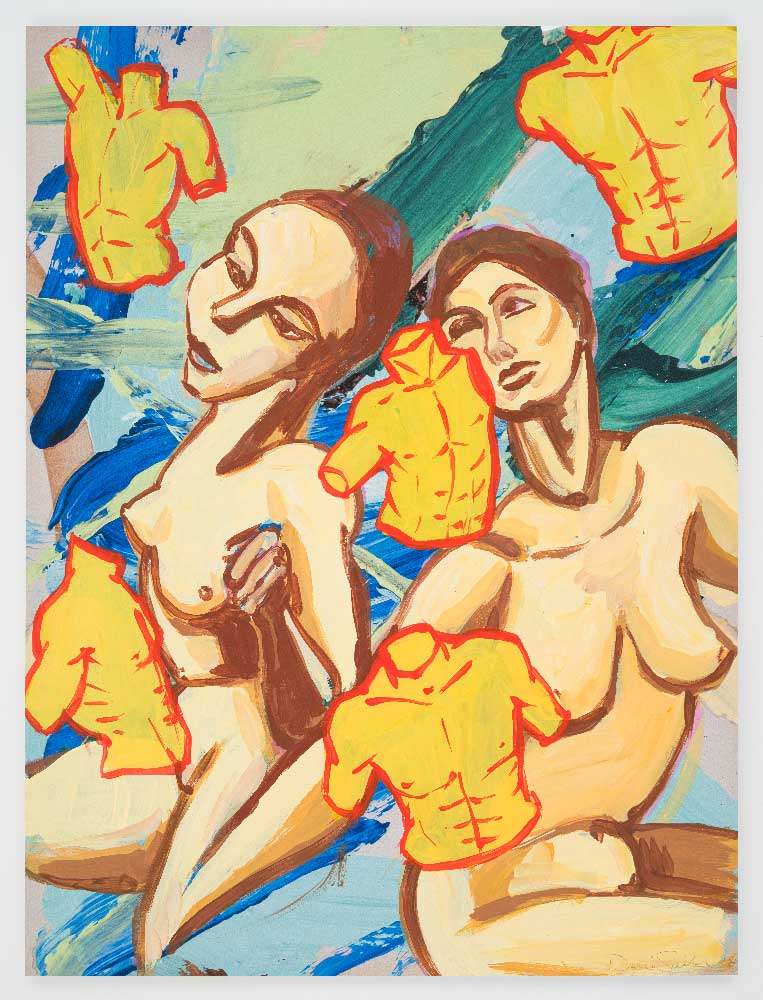

ALL WORKS: Untitled, 2023,

flashe, acrylic and pencil on paper mounted on aluminum (26 x 19 1/2 in.) © David Salle/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, NY |

"I was schooled in classical painting at a young age, and Hopper's work was then, and remains, a touchstone for how to translate the visual world into paintable forms,” writes David Salle. “One of Hopper's main concerns was for the way light and shadow can be used to create a feeling of lived experience. It is something I strongly identify with, as well as Hopper's 'American-ness', even though what we think of as American painting has its roots in France.

The famous solitude, one might even say loneliness, at the core of Hopper's work is something I also identify with, even if I arrive at it from a seemingly opposite direction. Where we differ of course is a matter of style and tradition. Hopper – like most realist painters – offers a compelling unity; one point of view, one time and place. My work is on the side of simultaneity – more than one thing, often more than five things, happening at once. However, if you really look carefully, there are several different things going on in one of his pictures. And similarly, although my pictures are built out of bits and pieces of lots of different sources and images, the end result, if it is to succeed, must also be highly unified. In these paintings, I'm interested in compression and concision – the haiku rather than the ode. I'm working not just with image juxtapositions, but also with pairings of scale, color, touch and so forth. I want to see one thing through another; the so-called 'background' is really another character." - David Salle |

Perhaps it seems incongruous to correlate the work of David Salle (b. 1952) to that of Edward Hopper (1882-1967). At first glance (and perhaps second or third), they appear to exist on opposite ends of the pictorial spectrum. Salle’s compositions are frenetic and lively, Hopper’s paintings restrained and discreet. Hopper deliberately planned his works far in advance of his paintbrush touching the canvas, while Salle composes his imagery mainly through intuition and builds his tightly choreographed paintings from a mélange of sources that include alluring bodies with layered and floating fragments taken from art history, New Yorker cartoons, and advertisements, and even mundane household items. “When I start a painting, I have no fixed idea of how it will end up,” Salle says. “It’s like a poem, additive line by line, image by image, phrase by phrase, until it reaches a sense of completion.”

Respectively, Hopper once said, “Originality does not reside in method, but is deeper seated in the personality and inner life of the artist.” While Salle and Hopper both acknowledge looking inward, Hopper’s stripped-down realism was not concerned with incorporating external art references or influential art movements around him, in fact he studiously ignored them. Despite the differences appearing on the surface of their respective paintings, Salle’s works reveal a call of recognition from one generation to another.

Respectively, Hopper once said, “Originality does not reside in method, but is deeper seated in the personality and inner life of the artist.” While Salle and Hopper both acknowledge looking inward, Hopper’s stripped-down realism was not concerned with incorporating external art references or influential art movements around him, in fact he studiously ignored them. Despite the differences appearing on the surface of their respective paintings, Salle’s works reveal a call of recognition from one generation to another.

Hopper’s characters are often seen through windows or from the darkness of their surroundings and viewing his paintings can be like watching a film paused, a narrative that will resume the moment moviegoers avert their gaze. Salle’s scenes intrigue viewers and draw them into a theatrical moment in which they may not otherwise participate, at once depersonalizing and even sexualizing the moment. If Hopper’s subjects depict quiet tensions of a theatrical scene, of energy coiled, then Salle’s work is the theater of action, of energy released. For Hopper, the cinema and Broadway were passionate pastimes, inspiring important canvases. Salle has a more direct experience with the stage in designing sets and costumes for opera and ballet: the movement of dance, music, and theater finds visual expression in his gestural brushwork and compositions.

Salle’s voluptuous and vulnerable figures echo, though perhaps at a louder volume, Hopper’s dramatically direct nudes. Hopper painted his first female nude, Summer Interior, in 1909 and created his last, A Woman in the Sun, in 1961; in between he etched Evening Wind in 1921. In each, the viewer is kept at a distance. Salle employs a power of a shrouded voyeuristic gaze as well, but his figures speak more of his artistic vision and hand. They too have an agency of their own yet demand to be looked at.

Salle’s voluptuous and vulnerable figures echo, though perhaps at a louder volume, Hopper’s dramatically direct nudes. Hopper painted his first female nude, Summer Interior, in 1909 and created his last, A Woman in the Sun, in 1961; in between he etched Evening Wind in 1921. In each, the viewer is kept at a distance. Salle employs a power of a shrouded voyeuristic gaze as well, but his figures speak more of his artistic vision and hand. They too have an agency of their own yet demand to be looked at.

Diving deeper another shared theme that appears is nostalgia. Both artists are adamant about the lack of specific narrative or intended symbolism – and influenced by, and responsive to, anxieties of their eras. Hopper worked through the Great Depression, World War II, and a fear and helplessness at the hands of an increasingly urbanized, modernized and commercialized society. Hopper always painted a personal vision of the world, with his most poignant images seemingly out of step with his own time. Yet, the personas of Hopper’s paintings do not look back but gaze inward or peer forward, never craving days gone by.

In contrast, Salle’s application of paint and collage and his layered source images divulge an enterprising nostalgia for iconic advertisements and cartoons from a bygone era of Madison Avenue marketing, not contemporary digital ones. For Salle, image overload, the bombardment of commercial branding and advertising campaigns in our culture, and the subsumption of our very existence into technology are concerns that have plagued society since the beginning of his career. In times of seismic cultural changes, Salle taps into this nostalgia to relay a different version of American identity, one that avoids the cliché, the saccharine, the overbearing, or the patriotic.

The art of David Salle, profound in his own legacy of influence, illustrates Hopper’s oft-quoted maxim, “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.”

In contrast, Salle’s application of paint and collage and his layered source images divulge an enterprising nostalgia for iconic advertisements and cartoons from a bygone era of Madison Avenue marketing, not contemporary digital ones. For Salle, image overload, the bombardment of commercial branding and advertising campaigns in our culture, and the subsumption of our very existence into technology are concerns that have plagued society since the beginning of his career. In times of seismic cultural changes, Salle taps into this nostalgia to relay a different version of American identity, one that avoids the cliché, the saccharine, the overbearing, or the patriotic.

The art of David Salle, profound in his own legacy of influence, illustrates Hopper’s oft-quoted maxim, “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.”

|

© David Salle/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, NY, Credit: Photo: Costas Picadas

|

ABOUT David Salle

Born in 1952 in Norman, Oklahoma, David Salle grew up in Wichita, Kansas. In 1970, he began his studies at the newly founded California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, where he worked with John Baldessari. After earning a BFA in 1973 and an MFA in 1975, both from CalArts, Salle moved to New York. In 1981 Salle designed sets and costumes for the opera. Birth of A Poet. Since then, he has designed for many ballets and operas staged around the world. In 1986, Salle was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship for his work in the theater.

Salle's first solo museum exhibition was at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam in 1983, and he has continued to evolve as a painter intent on integrating multiple points of authorial agency into an unprecedented gestalt. In the 1990s, he added sculpture to his oeuvre and began exhibiting his black-and-white photographs, many of which were made in preparation for canvases. He also directed the feature film Search and Destroy (1995), produced by Martin Scorsese and featuring Ethan Hawke, Dennis Hopper, and Christopher Walken. Salle’s paintings have been shown in solo exhibitions and in major international expositions in museums and galleries worldwide for over forty years His work can be found in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Guggenheim Museum, the Tate Gallery the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art, among others. In addition to his studio practice, Salle has frequently contributed writing to publications such as Artforum, The Paris Review, Art News, and New York Review of Books, among others. In 2016, he published the highly lauded book How to See: Looking, Talking and Thinking About Art, an incisive essay collection exploring the work of influential twentieth-century artists that has been described as “a master class on how to see with an artist’s eye.” In 2023, Salle began attempting to defy conventional thinking about generative artificial intelligence by testing an A.I. program’s capacity to become a sophisticated creator of art. Salle lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, and East Hampton, Long Island. |